Our Guide to Understanding the Dynamics of the 117th Congress

By: M Baqir Mohie El-Deen, MPAC Policy Program Manager

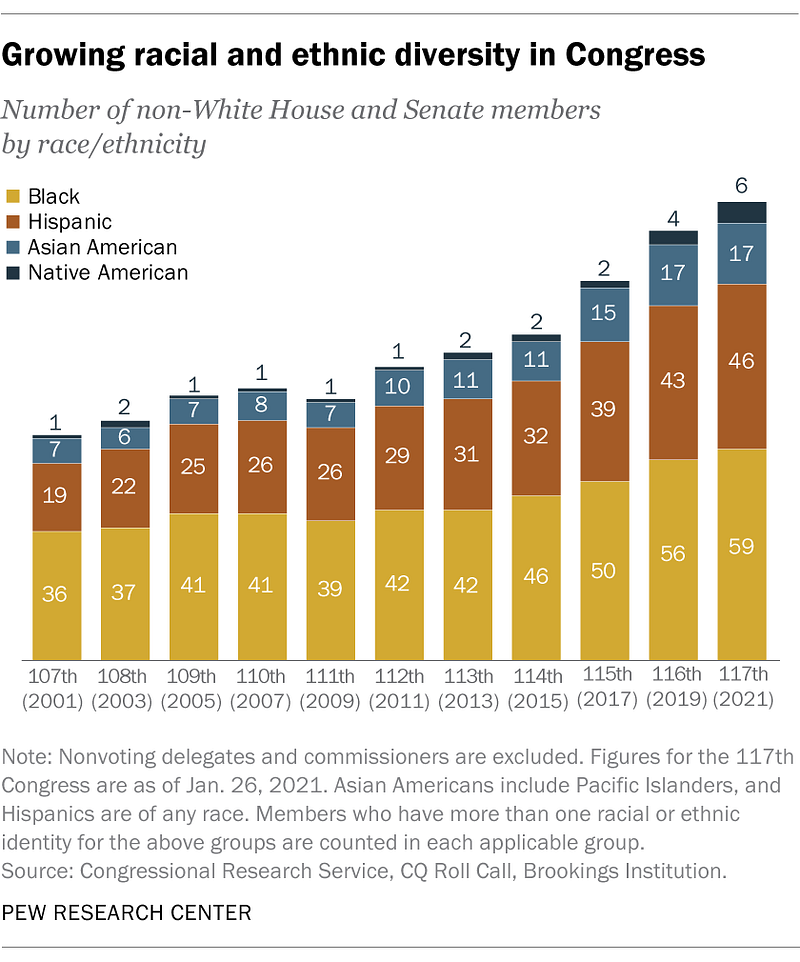

Welcome to the 117th Congress of the United States. This new congress has made history in many respects. This is the most racially and ethnically diverse congress in the history of our nation, with almost a quarter of the Congress identifying as either. But there is still room for more change. While we saw the most women in history elected into Congress, more than double the amount from even a decade ago, women form only a quarter of the 117th Congress. Non-hispanic whites account for 77% of this session, however they represent only 60% of the US population. This aspect of the racial gap has continued over the years: three decades ago, 94% of members of Congress were white while representing 80% of the U.S. population.

However, in the U.S. House of Representatives, some of the racial and ethnic representation are proportionate to their share of the American population. Native and Black Americans are both 1% and 13% of the U.S. House of Representatives and our population respectively. Other ethnic and racial groups, like Hispanics and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are both represented in the House of Representatives, which is half of their representation of the U.S. population, accounting for 9% and 3% of House members. The 117th Congress saw a drastic political and ideological shift of the new minorities elected into the House. Nine of the 16 freshmen house members are non-white Republican, compared with the 116th Congress, when only one of the 22 new representatives were Republican. Burgess Owens of Utah and Byron Donalds of Florida are the only two black Republicans in this freshman cohort.

This isn’t the only gain for Republicans in the House. Republicans shocked political strategists by gaining 13 seats in the House, decreasing the Democratic majority from 33 to just 10. The Freedom Caucus, formed in 2015 by remnants of the Tea Party, gained eight new members bringing their total to 45. Some of the freshmen Freedom Caucus members unseated centrist Democrats, while others gained their victory by unseating centrist Republicans in the primary. This shift reflects that President Trump’s ideology has outlived his presidency — not only leaving behind a divided America, but a divided GOP. Overall, the Republicans’ victories that have puzzled many are said to be explained by two reasons: either the 2018 election was so spectacular for Democrats that it was unreasonable for them to expect 2020 to increase their lead, or that many Biden voters failed to vote for congressional candidates.

The first explanation: the 2018 midterm elections saw the highest turnout in more than a century. Many Americans turned out to vote in droves due to their opposition to then-President Trump. Additionally, Republicans weren’t as persuaded to head to the polls in 2018 with Donald Trump occupying the White House, seeing a 20% decrease in their turnout from the 2016 election. That year’s almost 10 million more votes for Democratic candidates created a margin of 8.6%, the largest margin ever for the party, creating a spectacular year for Democrats in 2018.

As for the second explanation, the numbers reveal a much more straightforward reason. While the total votes cast for Republican House candidates were 1.4 million less than for President Trump, Democratic House candidates saw a staggering 3.9 million votes less than the votes cast for President Biden. The total votes cast for Republican House candidates in 2020 was 1.4 million less than for President Trump, while the total votes cast for Democratic House candidates fell short of Joe Biden’s total by 3.9 million. Biden’s margin over Trump was 1.5 percent greater than House Democrat candidates’ advantage over House Republican candidates, which would explain why the down-ballot shortfall made it more difficult for Democrats to gain victories in close elections.

Moving on to the Senate: Georgia saw two new Senate victories in their state’s runoff election, which ultimately handed the Democrats control of the Senate, but by a slim margin. The last time we witnessed a split Senate was with the 2000 election. A split Senate gives control of the chamber to the party presiding over the White House, with the Vice-President being the deciding vote. Following the precedent set by the 2001 Senate, earlier this week, Minority Leader Mitch McConnell broke the news that the Senate approved a power-sharing agreement that allows Democrats to take control of committees, but with equal members of each party in each committee.

What do the new dynamics of the House and the Senate mean?

In simple terms, it means that bipartisanship is now more important than ever for more effective legislation to pass. Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Majority Leader Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY) have to court the support of the centrists from the opposition party, at the expense of the far-right and left from their own party. Although the far-left Progressive Caucus gained two new members in the House, Speaker Pelosi (D-NY) may have to disregard their support for the sake of gaining centrist Republican House members’ support to pass legislation. This creates a massive barrier to achieving President Biden’s campaign promises for sweeping reforms on legislative issues such as healthcare and climate change. The Democrats’ razor-thin majority margin in both chambers of Congress increase the Republicans’ ability to obstruct meaningful reform. As an example, 60 Senators are needed for the filibuster to be scrapped. However, since only a simple majority is needed for judicial nominees, the Democrats will have an easier time getting nominees confirmed, and the same goes for granting statehood to D.C., or Puerto Rico, if the Democrats wanted to venture down that path. The Biden Administration will also be able to avoid harassing probes with Democrats leading over Senate committees. Significantly more important, the new majority leader, Sen. Schumer (D-NY) now has the power to control which bills are brought to the floor for a vote and control of the Senate calendar.

While most are looking towards the reform that the Biden Administration promised on the campaign trail, many are already eyeing the 2022 midterm elections. Historically, midterm elections always see a swing vote towards the party that’s not occupying the White House, and a President’s success is typically measured by their ability to decrease the inevitable swing to the best of their ability. This is worrisome for the Democrats. A razor-thin Democratic majority leadership in both of the congressional chambers may indicate a stark future for President Biden’s last two years, potentially having to preside with a Republican-led Congress. This potential future may more so motivate the GOP Congressional members to obstruct meaningful reform via legislation. In 2022, Republicans can capitalize on that stalemate to campaign on the notion that the Democrats could not enact any noteworthy laws despite controlling both chambers of Congress and the White House for the past two years. As we wait to see what the next two years will reveal for legislators, one thing is certain: it will be well-advised for Democratic strategists to solve the discrepancy that occurred last year between the votes for President Biden, and the lack of votes for Democratic House Candidates.